Brugada Syndrome

This is a genetic disease, linked to an anomaly in the ECG, reported for the first time in 1992 by the Brugada brothers. Its prevalence is of 5/10000 people, with five-fold higher incidence in male than in females, especially among people of Asian descent. It is thought to be responsible for at least 4% of all sudden deaths, and up to 20% among people with structurally normal hearts.

Although many different mutations have been related to this syndrome, one of the most prevalent is the mutations in a gen (SCN5A) that regulates the inactivation of the cardiac sodium channels.

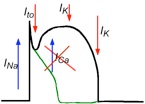

Now, why does it happen? Alright, let us look first at the action potential of a cardiac cell.

Simplifying, there are two main inward currents, the sodium current INa, responsible of the depolarization, and the calcium current, ICaL, that gives rise to the dome; and several outward currents, of which, the potassium transient outward current is responsible of the notch, and a series of potassium currents produce the repolarization of the cell. If the sodium inactivates too fast, then the transient outward current is enough to decrease the value of the transmembrane potential below the onset for the opening of ICaL, and the dome is lost.

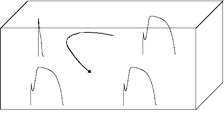

The most plausible hypothesis nowadays proposes that this is due to reexcitations arising from dispersion of repolarization, i.e., regions where the AP has lost the dome become rapidly excitable, so the regions with normal dome reexcitate them, producing a reentrant loop. This maybe the origin of a tachycardia that, in the worst case, can degenerate into ventricular fibrillation and sudden cardiac death.

In fact, the typical elevation of the J segment of the ECG is due to a regional shortening of the AP in the ventricles.

Antzelevitch & Fish, Basic Res Cardiol (2001)

Good, so we know why we get this ECG, but why is it dangerous?